A quick backstory:

The previous Labour government amended local government law to introduce Māori wards—an effort to honour the Treaty of Waitangi’s principle of partnership.

That change also removed a discriminatory provision: councils could create wards for specific demographics (e.g., rural wards) without challenge, but Māori wards could be overturned if just 5% of voters demanded a referendum. Only two councils ever cleared that barrier.

The current coalition government campaigned on reversing those changes.

Their legislation reinstated the referendum requirement, meaning councils must now hold a binding poll if they wish to retain Māori wards established since 2021.

They got elected—and followed through.

Here we are

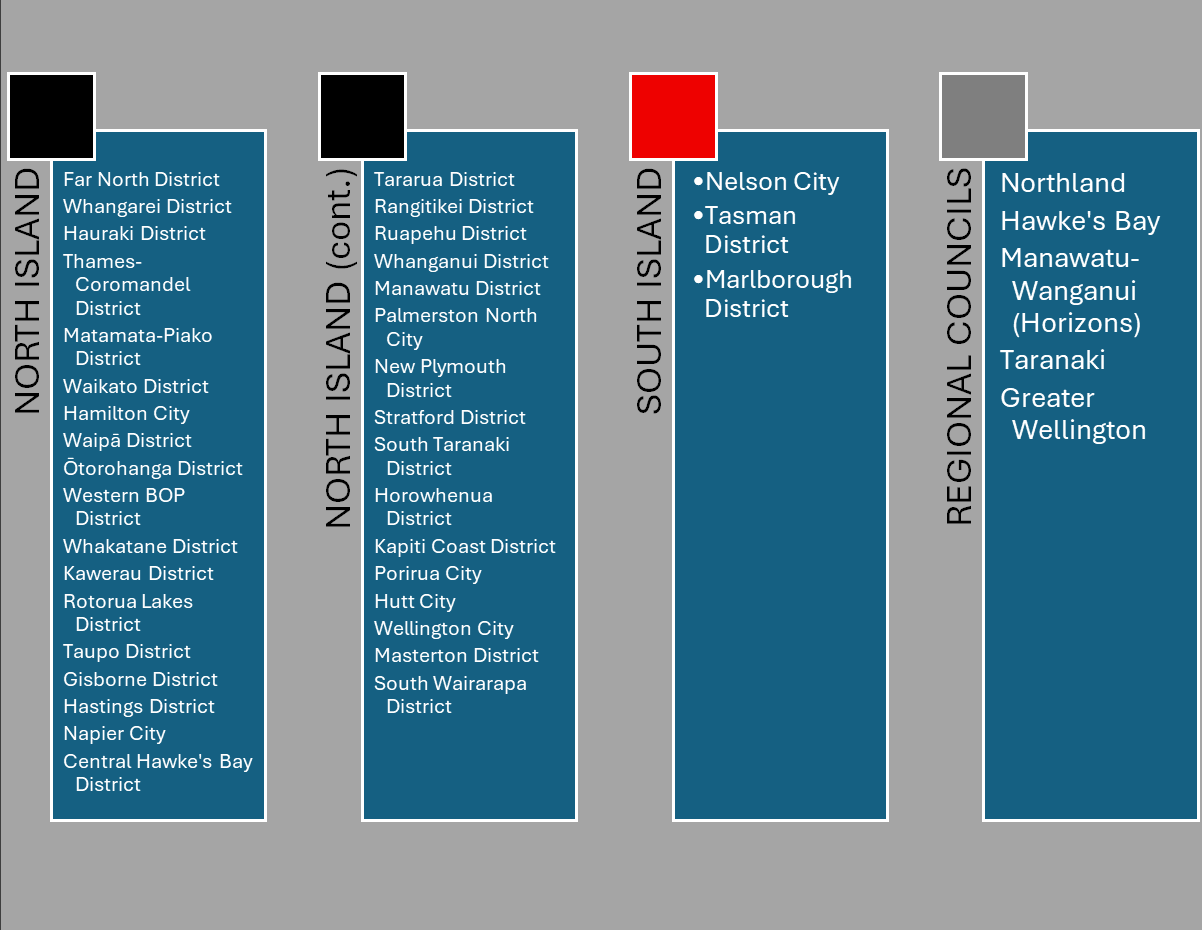

Aotearoa has 78 local authorities: 11 regional councils and 67 territorial authorities (district and city councils).

Of these, 34 created Māori wards ahead of the 2022 elections, and another 11 voted to introduce them in future elections, including 2025.

All now face a referendum this year—except Kaipara and Upper Hutt. (Kaipara voted to disestablish its Māori ward; Upper Hutt rescinded its earlier resolution to create one.)

In affected areas (graphic below shows councils holding a referendum), voters will elect mayors and councillors in October—and vote on whether to keep or remove Māori wards. The ballot will include two options:

- “I vote to keep the Māori ward/constituency”

- “I vote to remove the Māori ward/constituency”

What do councils do?

Local bodies handle essential services like roads, water, sewerage, rubbish collection, planning—and community assets like libraries, pools, playgrounds, and skateparks.

They also have a duty to consult and collaborate with mana whenua, iwi, and hapū on matters affecting those groups, in line with Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Māori wards were intended to uphold the Treaty’s partnership principle, enabling Māori voters to elect representatives to the decision-making table.

What’s at stake?

At stake is direct representation of Māori, iwi, and hapū interests in local governance.

While elected Māori ward councillors aren’t guaranteed to champion every Māori issue, they are chosen by Māori voters and are more likely to reflect those priorities.

The referendum outcome—decided by a simple majority of all eligible voters—will determine whether Māori wards remain in place for the 2028 elections.

That’s the challenge: the decision lies with the general electorate, not just Māori roll voters.

Voices of faith and justice

Retired Anglican Archbishop Sir David Moxon was among 100 church leaders who voiced support for Māori wards this week, drawing criticism from Deputy Prime Minister David Seymour.

Sir David told the NZ Herald his support stems from a moral obligation to honour Te Tiriti:

“Since the Anglican Church, supported by other churches, did host, translate and promote the Treaty from 1840 onwards, it was our word, our sermons, our personnel, our networks that enabled this covenant, this partnership, this interdependence to form the basis of our democracy and nationhood.”

Why it matters

Voter turnout in local elections has long been low—especially among Māori.

In 2022, South Taranaki’s overall turnout was under 40%; Māori turnout was barely a third of that.

In one district, the lowest-polling mayoral candidate received 2,000 more votes than all Māori ward candidates combined.

This reflects not just roll numbers, but the uphill battle Māori candidates face in general wards.

History shows that outspoken, pro-Māori advocates often struggle to win against general candidates.

People have marched for Māori rights, te Tiriti, and other kaupapa since this government took office. But the most powerful action is still the simplest: vote.

Every vote counts—especially this year.